Ever wonder what scientists talk about at a cocktail party? Being types focused on what they are focused on and not given to chitchat, I doubt they even notice the sauce on the toothpick-skewered cocktail weenies or pause in their deep deliberations to compliment the hostess on her light touch with the gorgonzola cheese foam sabayon.

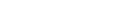

While the rest of us – inextricably devoted to our mundanity – are still waxing sniffy about Germany’s World Cup victory, could it be that over in the corner the grouped geologists, paleontologists, glaciologists and geomorphologists have unanimously agreed that 150 million years from now Africa will run headlong into Europe, thus creating a Himalayan-sized mountain range where Madrid, Rome and Athens used to be?

The idea of this eventual “bumper car” collision is not new. It’s happened before. Currently the planet is inching toward the traffic jam of Pangaea II. But you can’t have a Pangaea II without a Pangaea I, so it’s necessary to consider what happened during the first go-round.

The planet Earth is more than 4 billion years old. To put Pangaea I into perspective, the mass link-up of all land on the planet occurred not at the dawn of history, but took place around the brunch time of history.

About 200 million years ago there were no countries divided by borders or seas or checkpoints controlled by guards with machine guns. The world had no Canada, no South America, no China, no Russia and – hard as it is to believe – no Middle East. What we did have was one giant super-continent. Every piece of dirt on the planet was joined together.

Just imagine, if there had been people at the time, they could have walked from New York to Paris, could have strolled from Rio de Janeiro over to Johannesburg, skipped from Sydney to Singapore and could have maybe ridden a dinosaur from New Delhi to Dubai. Imagine even more: Snowbirds from the U.S. Northeast could winter in Miami and at their leisure mosey over to Atlantis for lunch.

And that brings me to the subject of culinary fusion.

Could it be that inside the human memory bank there is deposit box that is filled with recollection of, for wont of a better description, the first things? In this case, the first things being that time in history when the surface plates of the Earth were slammed together. The fact is, 200 million years ago the ultimate globalization existed. Scientists might call it Pangaea I, but for those of us who like clarity and simplicity, it might be best to think of the giant landmass as The United States of Everywhere.

And when Everywhere is packed close together, the natural result is a One World dining experience.

That idea will be developed later, but first let’s talk about God. The Creator might have invented the word gourmet, but He wasn’t one.

For instance, that He scattered 7,500 varieties of apples across the globe was nice, but He forgot to throw in a recipe for tarte tatin. It wasn’t until the mid-1880s, when the gastronomically adept Tatin sisters of Lamotte-Beuvron, France, accidentally burned their baked apples and quickly thought to disguise the error with a buttery pastry crust did a gourmet-type apple dish come to the world kitchen.

In the beginning what mostly interested God was bringing forth (in paraphrase) the dry land, clear of the waters, and to drop seeds upon the dry land and a bunch of herbs too and fruit-bearing trees. Every fish of the sea, every bird of the heavens, every bit of livestock and even the creeping things on Earth shall be food.

Knowing that down the line at some point humans would pop up and want to eat, God gave the joined United States of Everywhere everything anyone could possibly want for dinner. Plus, He made dining out convenient because every sort of food on the planet was within walking distance.

It’s interesting to note that the same fossilized plants and animals are shared by both South America and Africa. With boundaries eliminated during Pangaea I, the planet’s grocery store had succulent, meaty herbivorous sauropods available for diners in both Colorado and Tanzania, and T-Rex (an even larger meat dish) might have fallen to a caveman’s spear – if there had been cavemen, of course – in both Phoenix and Mongolia.

Looking closer at the big picture, during Pangaea I Australia was connected to Antarctica and, most surprising of all, Spain and France were once nestled up close to Venezuela. Both Britain and the North American Appalachians have similar coal deposits; and the wondrous Himalayas rose to glory when India rammed its bumper car into Asia.

The word foreign had no place in the world 200 million years ago. If culinary fusion means to cook using ingredients from wildly dissimilar cultures – a kind of East-meets-West thing – during Pangaea I, the world kitchen was filled with kindred chefs who understood the shared miracle of fire would turn raw into cooked no matter where you lived.

In our current epoch there are 1.9 million plants, animals and, yes, the creeping creepy things on the planet Earth. Some comestibles may be considered foreign to us. Some people over here may think the food from over there is strange and unpalatable. Some noses may be turned up; some mouths may sneer with distaste.

However, that Africa has been sneaking up on Europe for the past 40 million years – that Australia is headed toward Southeast Asia, and the Americas are drifting toward the new Euro-African continent – when the day comes that the Mediterranean Sea disappears and the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans pucker into mere mud ponds – Brazilians will eat whale with relish, the Watusi will chow down on Swedish meatballs, the word Chinese will be dropped from the menu and replaced with simply food in the Column A slot, and folks in Mississippi will go nuts for a dish of babaghanoush.

Cultural culinary con-fusion will be a sad condition of the bordered past. Suspicion of the plate and fussiness about what’s on the fork will disappear. And no hip, modern diner will ever again ask the waiter, “What the hell is this?”

Follow Us